February 6, 2010

Welcome to our Blog

Background on Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind - Female

Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger and Tarule’s (1986) theory on women’s cognitive development stemmed mostly from Perry’s (1970) and Gilligan’s (1982) previous work. Perry’s research (1970) focused on areas of cognitive development and whereas Gilligan (1982) researched women’s moral and personal development. The outcome of the new research resulted in Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind (Belenky et al., 1986, (Love, & Guthrie, 1999). Tarule (1997) later concluded that the results of the study were related to gender but not gender specific. Despite its criticism, the study did contribute to the study of cognitive development theories because it examined social classes, women, and differences significant in society (Love, & Guthrie, 1999).

Description of Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind - Female

This theory illustrates five perspectives, in which women view themselves and the world, and how they make meaning of their life. The theory found that there were many outside influences such as “race, class, gender, ethnicity, physical ability, sexual orientation, and regional affiliation” that played a role in the formation of one’s cognitive development (Belenky et al., 1986, (Love, & Guthrie, 1999). Research for this theory was conducted by exploring the ways participants formed their way of knowing. There were 135 female participants from urban and rural areas represented in the study. Participants were from a variety of educational levels, age (sixteen to sixty), ethnicity's, and class were represented.

Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger and Tarule concluded that women progress through a series of five epistemological perspectives. The researchers note that the perspectives are not stages and an individual cannot stay fixed in one perspective. It is also important to point out that the theory is not universal because it cannot address the complexity of each individual’s life (Love, & Guthrie, 1999).

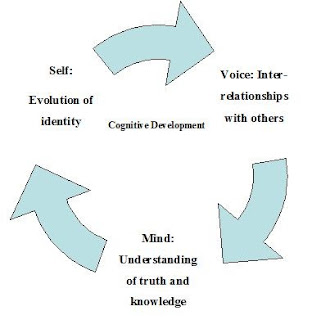

The researchers describe cognitive development as a relationship between the self, voice, and mind. The diagram below is developed to provide you a visual representation of the formation of cognitive development.

The Five Epistemological Perspectives as described in Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind:

Silence:

As the title suggests, in this perspective women lack a voice because of their dependency on authority to speak for themselves due to low sense of self or isolation, among other reasons. Goldberger (1997) describes this as a way of not knowing. The women in this perspective had several characteristics in common such as experiences of abuse and violence; combined with the incapability to form their own thoughts and lack of confidence to learn from experience, these women failed to develop a mind of their own. This perspective does not have to be present for cognitive development but is acknowledged as a common starting point for many women.

Received Knowing:

Women at this perspective have begun to learn from listening to authorities. Their method of learning is by receiving, memorizing, and mimicking words from authorities. Because of the regurgitating of others’ words, women have trouble creating “original work.” To these women, the world is in black and white, no gray areas, and they either understand and idea or they do not. Women are unsure about their knowledge as they look to others for it and as a result they lack confidence in speaking.

Subjective Knowing:

Here, women are developing their self and voice, two of the main factors for cognitive development (mind). Their inner voice was the catalyst that ignited the change towards becoming more active as a subjective knower. A power shift is occurring, as women become the authority. As their own authoritative figure, women use their own experiences as the basis for knowledge and truth. The learning method here is more proactive by immersing themselves into the world to create new experiences.

Procedural Knowing:

The women in this perspective recognize that they need “procedures for knowing”; these procedures include the examination of authority and external truth (Belenky et al., 1986). The authorities for women in college are those who hold positions within their institutions and so they make an effort to recognize new authorities. Procedural knowers speak with both of the following voices:

- Separate knowers: looked for and analyzed knowledge by justifying it. Separate knowers looked beyond the object of knowing; they were separate from it and then make their evaluations. They utilized the “doubting game” in which they doubt all knowledge until proven “worthy” (Belenky et al., 1986).

- Connected knowers: the main goal of the connected knower is to understand. They accept the perspective and opinions of individuals, acknowledge the “worth” in them, and pay attention to details. This method is described as the “believing game” and they employ it because they are actively trying to understand the other person

Constructed Knowing:

After a period of self-reflection, women arrive at the last perspective. This is the result of the incorporation of the three components for cognitive development: self, voice, and mind. The women here are conscious about themselves and others and they give attention to what goes on internally and externally. They have the ability to carry on significant dialogue by responding with active listening and talking. The women accepted previous ways of knowing because they acknowledge that the past can provide them with different results.

February 3, 2010

February 2, 2010

Applying the Theory in Higher Education - A Case Study

In an effort to show how a leader in higher education would apply this theory, we created the following case study:

As a dean within a higher education institution, I have seen various instances where the knowledge and application of Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule’s Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind (1986) would have been of great use. The theory (presented above), addresses female development through five epistemological perspectives, providing insight to the experiences and thoughts female students may be encountering in their personal identity search. Students entering higher education are faced with numerous opportunities for growth, however campus leaders and authority must be prepared to challenge, nurture, and support this process.

As outlined by Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule (1986), institutions must recognize several aspects of their perspectives including: the need for some women to reject their past, the role of sexual harassment and abuse in some women’s lives and the influence this has on development, and the possible disconnect from authority. Given a breakdown of the epistemological perspectives, it becomes the institutions responsibility to provide training and tools to help advisors, faculty and other campus figures address and respond to a student’s individual position. Campuses can provide outreach and support for those having suffered abuse or harassment (silence perspective) as well as create additional opportunities for female students to actively participate in planning and execution of various projects (subjective knowing).

It is now clear to me that institutions must equip campus leaders or authority figures with the ability to interact with female students in a non-threatening manner, allowing for continued development. Over time, campus leaders such as myself will receive training and support on ways to interact and communicate with our female students based on their varying perspectives. This training will aid in student/staff interactions, ranging from classroom debate to advising, ultimately allowing a deeper identity development.

February 1, 2010

Evaluation of Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice and Mind - Female

In this theory there was a strong focus on the dependence of authority which at times felt overwhelming. The research suggested a relation between social class, and the perspective of cognitive development that the participants were in. Often the generalizations made about the participants past could have a different outcome for various individuals. Ultimately it is important to point out that each individual is different could be in a range of each of the perspectives it is ultimately to complicated to fully capture the complexity of each individual.

Background Davis’ Social Construction Theory - Male

Description of Davis’ Social Construction Theory - Male

Importance of Self-Expression:

Males feel that self-expression and communication are very important to them. However, being comfortable with self-expression was not always practiced earlier in life.

Code of Communication Caveats:

- Communication with women - Men are more likely to openly express themselves to women than men. However, there is some perceived fear of being penalized in terms of a woman considering a male as a potential partner if he is too expressive. For example, some of the men interviewed believed that “you’ve got to be jerky to women” because being too nice means you’re more likely to be perceived as a spouse than a potential boyfriend.

- One-on-One communication with other men- As opposed to communicating with other men in a group where a level of performance through humor or insults is expected, men are able to have more intimate discussion with another male when the conversation is one-on-one. This may be due to fear being accepted by the group or appearing overly effeminate.

- Nonverbal and side-by-side communication –Upon engagement in an intimate conversation with another male, men are likely to show affection by a nonverbal, physical cue such as a squeeze on the shoulder or light punch in the stomach. The logic behind this is that if the male doesn’t feel like he can hit you, then he doesn’t trust you as a friend. Side-by-side communication is a way men communicate with each other as opposed to face-to-face, such as in a car ride, playing video games, or watching a show on television. The men report the significant of the relationship in the context of the activity they are engaging in, but discussion was found to hold meaning outside of the activity.

Fear of Femininity:

Men have expressed fear and frustration of femininity outside of expression and communication styles. They do not want to come off as being “unmanly” and often feel the need to prove themselves. Men are also concerned of behaving in a manner that would have other people questions their sexual orientation, such as talking a lot and wearing certain clothing styles because they perceive a social message that links feminine activities with homosexual traits and want to avoid these labels as such.

Confusion About and Distancing From Masculinity:

Men do not often report thinking about what it means to them to be male (Davis, 2002). It seems they give very little thought to this part of their identity. Men also do not view themselves as being a typical male, for example they do not consider themselves to be “macho” and value the relationships in their lives. Therefore, it appears men do not actively think about what it means to be a man, and they also do not want to identify with being what their perceived definition of masculine is.

Sense of Challenge Without Support:

Several men feel there are not equivalent resources on campus available to them, whereas there are resources specifically designed for women (e.g., women’s center, women’s leadership programs). Both genders may face the same challenges in the classroom, but males identified situations where females received more support from faculty, such as asking a professor for help with physics homework.

Applying the Theory in Higher Education - A Case Study

Davis suggests academic professionals develop programming designed specifically “to put gender on the radar screen for men”. The goal of this would be to provide a setting where men can learn about and discuss what it means to be a male in college. This would include opportunities to identify the code of communication caveats listed by Davis and find ways to resolve and work though them. Additionally, programming could be utilized to explore issues like the feminine/masculine overlap that many males struggle with on a daily basis.

Another application of Davis’ theory is to give men an outlet for support. Traditionally men do not have a “safety-net” in place on campus. Davis eludes to Pollack’s work stating we as student affairs professionals must be aware of all our students’ dispositions regardless of their gender. Just as other groups on campus have support systems, so too could we provide one for men.

Finally, we must re-think the communication channels and methods when working with our male students. From Davis’s work we learn that men prefer less group talk and more one-on-one communication. This understanding is key for all professionals who engage with students and must be taken seriously if we are to give men the same guidance as our other student populations. Davis also shows how men are able to express themselves better while engaging in a form of activity. Simple methods like taking a student on a brief walk outside of the office can go a long way in “providing alternative pathways of expression” that so many of our males need.

Each of these small applications will go a long way in improving the developmental circumstance of males at our institution. Men struggle through the collegiate experience due in large part to the way they feel about themselves and the way they believe others perceive them to be. As student affairs professionals we can help move men from a social constructed identity, to an identity formed through self-authorship.

Evaluation of Davis’ Social Construction Theory - Male

There are several critiques of this theory. Firstly, Davis supports this theory from data she collected from only ten white, traditional aged students from the same university. This limited sample size is very unlikely to be generalized to the diverse population of male American college students across the United States. The ten males were also referred to Davis by student affairs professionals who were asked to identify students who were reflective about gender issues or currently struggling with their own gender development. This effort to recruit through people who are able to identify participants of particular interest to the researcher creates a biased sample and should be considered when assess the validity of Davis’ theory.